While strolling through the grocery aisles recently, I headed down the pet food aisle to grab some dog food.

While strolling through the grocery aisles recently, I headed down the pet food aisle to grab some dog food.

I should confess that I don’t actually have a dog – but I do have a voracious family of crows that knows I’m a sucker. So I keep myself stocked with treats to stay in their good graces.

But I digress….

As I made my way down the aisle, I passed a number of traps & other contraptions aimed at managing resident rodent populations. And while normally I don’t pay them any mind, this time one in particular caught my eye.

Now, we could go in circles arguing about whether you “should” kill mice, whether they have a “right” to exist or any number of similar points – but I’m not interested in arguing.

Because mice can inflict damage to your home & belongings, and I understand that many people feel that removing them permanently is the best course of action. Especially when you’re talking about electrical damage that puts your family at risk or hundreds of dollars in damage to your car.

And in those cases, I’m not going to object to the use of quick traps or other lethal methods that end their lives swiftly.

But bait stations are another story altogether.

How they work

As you’d expect, bait stations are specifically designed to attract rodents, which is why many brands include flavorings such as fish oil, peanut butter, molasses, grains, meat or fruit. And once attracted, the animals will consume the bait as readily as they would any other edible – making it a “simple solution” to knock them out.

Or so the manufacturers would have you believe.

Many of the common rodenticides, including bromadiolone, chlorophacinone, difethialone, brodifacoum & warfarin, are anticoagulants. In short, they inhibit an enzyme that affects the activity of Vitamin K in the production of clotting factors in the liver, which ultimately causes the animal to bleed to death internally.

And as you can imagine, this process isn’t immediate.

It can take several days for enzymatic activity to be impeded. During this lag, they continue to consume the bait, which leads them to ingest far more than the lethal dose.

But eventually the poison takes its toll, and the animal becomes slower & less agile. In turn, it is much more vulnerable to nearby predators & scavengers that are all too happy to take advantage of an easy meal.

Why rodenticides are bad for wildlife

When predators or scavengers make short work of a dead or dying rodent, they don’t just land a full belly.

When predators or scavengers make short work of a dead or dying rodent, they don’t just land a full belly.

They also end up with lethal or sublethal secondary poisoning.

And because the rodent likely consumed several times the lethal dose during the latent period, the predator is slammed with a super-dose of toxins.

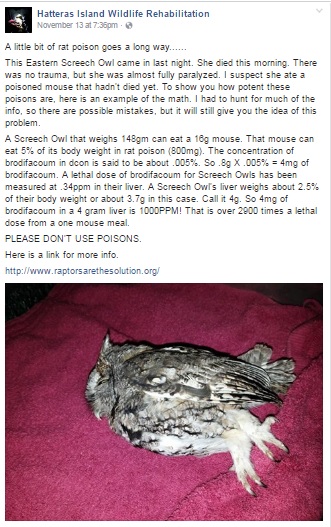

Depending upon their size & the amount of poison they consume, one meal may be all it takes before they suffer the same agonizing fate as the rodent, hemorrhaging internally over the course of several days.

In other cases, the poisons may accumulate over multiple meals, which may sicken but not kill them. At least not right away.

And when those animals die, other scavengers or predators such as turkey vultures, raccoons or crows are happy to help themselves to the carcass.

This rapacious cycle is precisely why these poisons are a nightmare. And unfortunately, they lead to hundreds – if not thousands – of deaths each year.

Calculating exact numbers is difficult given the nature of the problem. These bait stations are available online & in stores throughout the country, so researchers cannot readily identify who purchases them or where they are placed.

Second, these deaths are largely unnoticed unless a person finds a sick or dead animal & brings it into a rehabber or vet. Further, unless a vet performs a necropsy, there’s no way to know whether these poisons were in its system. And given that these tests can run $200 or more, they are not often conducted.

But researchers are beginning to piece together the prevalence of their impacts, and it isn’t looking good:

- of the 161 raptors tested at Tufts Wildlife Clinic in a study between 2006 and 2010, 86% had rodenticide residues in their liver tissues.

- 19 of 21 fishers sampled in the Sierra Nevada National Forest & Yosemite National Park tested positive for traces of rat poison (and one died).

- since 1994, the California Department of Fish & Wildlife’s Wildlife Investigation Laboratory has confirmed at least 400 cases of wildlife poisoning from anticoagulant rodent baits

- researchers at the University of California found second-generation anticoagulants in 70% of mammals and 68% of the birds they examined.

Though some states & communities have called for a ban on anticoagulant rodenticides, few have been successful. Moreover, they’ve received notable pushback from manufacturers that aren’t keen on seeing their products banned from local shelves.

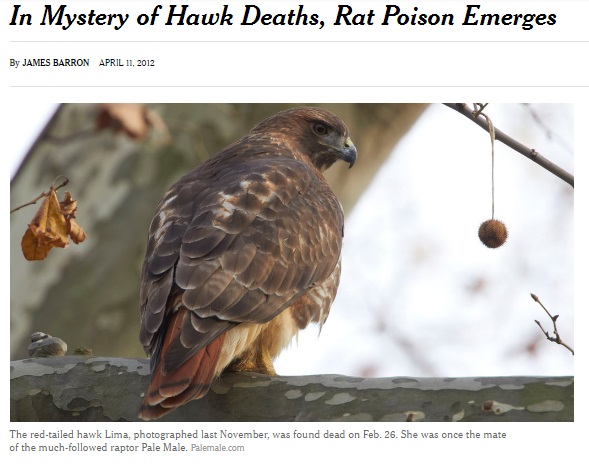

In the meantime, we continue to see stories & headlines like these:

What you can do

First & foremost, if you have a problem with rodents in your home, never use bait stations as a solution. If you need to control the rodent population, there are a number of alternatives available.

Options include:

- Erecting owl boxes nearby.

- Using single or multi-use traps.

- Using Have-a-Heart traps.

- Installing sonic pest repellents.

- Not hunting or otherwise discouraging predators such as coyotes, foxes, hawks & owls from your land.

- Some people have had luck planting mint around their homes to discourage rodents.

You can also visit www.SafeRodentControl.org for more options & information.

Second, check your local stores to see if they are selling bait stations. If so, contact an owner or manager to let them know why these rodenticides are dangerous for local wildlife & urge them to remove them from their shelves.

When you make contact, remember that many people are genuinely unaware of the domino effect these poisons create. So be polite but informative, and remind them that we all need to work together to maintain healthy communities for humans & wildlife alike.

For more information:

Raptors are the Solution (RATS)

Poisons used to kill rodents have safter alternatives via the National Audubon Society

Raptors & rat poison via Cornell’s All About Birds